Whither Contract Labour Abolition? From Rise to Repeal – A Paper By Sudha Bhardwaj

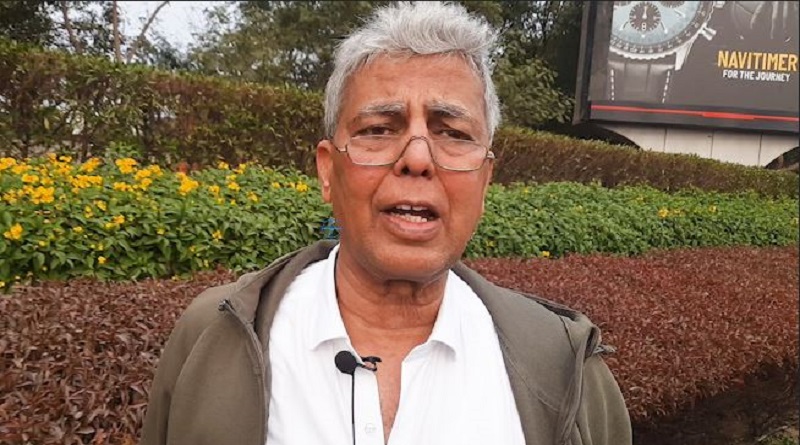

By Sudha Bhardwaj

The Contract Labour (Regulation & Abolition) Act, 1970 (CLRA Act) is a unique piece of Indian labour legislation, possibly unparalleled in the world.

As labour laws have been passed, improving the conditions of labour in the organised sector in the decades following independence; industrial establishments have been increasingly resorting to the device of contractualisation – that is of subcontracting out the work of their establishment to contractors – in order to obfuscate the “employer-employee” relationship and to avoid their liability/ responsibility as employers.

Such precarity of labour brings in its wake – (i) almost insurmountable obstacles to unionization and “recognised” collective bargaining; (ii) a glass ceiling separating two sections of working class – the permanent workers and the contractual workers – which become, as Jonathan Parry and Ajay TG so graphically describe in their book “Classes of Labour” on labour in the Bhilai Steel Plant, almost two different classes, with all the consequent political implications; and (iii) an extremely poor standard of living of a majority of the working class even in the organised sector, devoid of benefits of most labour legislation.

The declared objective of the CLRA Act was to abolish contract labour wherever possible, and to otherwise regulate it. It restricted the conditions under which contractualisation could be resorted to, facilitating the prohibition of contractualisation where work was perennial, necessary to the enterprise, and regular in nature. It defined a “Principal Employer” in the context of a “Contractor” and laid down certain responsibilities upon this Principal Employer – in particular ensuring the timely and full payment of wages – but also of keeping the Labour Department apprised of the particulars of contractors it had engaged, the numbers of workers under such contractors, and the details of the nature of work entrusted to them. It laid down certain conditions to be fulfilled by the Contractors, and certain amenities that such Contractors were bound to provide to workers.

It empowered governments (both Central and State) to abolish contract labour in specified processes in specific industries under their administrative control, in consultation with tripartite boards having representation from labour, management and the government. It laid down a process whereby an enquiry could be conducted by a tripartite committee whether contract labour should be abolished in a particular process in a particular industry or not. (The criteria were to include whether such work was necessary and incidental to the work of the establishment, whether it was perennial in nature, whether it was ordinarily performed by regular workmen and whether it was sufficient to employ full time workmen.) Such legislation is absent even in the most advanced capitalist economies.

However, it is equally evident from the ever-increasing levels of contractualization in the organised sector in India today, and the poor wages and miserable conditions of work this has spawned, that the CLRA Act has not succeeded in achieving its declared objective. Why was this so?

Were there weaknesses and loopholes in the manner it was drafted? Did the fault lie in implementation? Or were the judicial interpretations of its provisions to blame? Perhaps a combination of all three. If anything, all these needed to be rectified, and the implementation of the Act needed to be strengthened in order to assure a basic minimum standard of wages and working conditions in the industrial sector.

However, quite to the contrary, 52 years after the passing of the Act, it is on the verge of being repealed by the “Occupational Safety and Health Code, 2020” (henceforth OSH Code) – a piece of legislation which has nothing in its statement of purpose to do with the aims and objectives of the CLRA Act. Nor are any other commensurate provisions being provided in the new Labour Codes. Literally the baby has been thrown out with the bath water.

As a trade union worker since 1984, I have been continuously working with contract workers, both in the public and private sectors. During this period, I have observed or participated in, three major struggles of non-regular workers:

The struggle for the departmentalization of contractual iron ore miners in the captive iron mines of the public sector Bhilai Steel Plant, at Dalli Rajhara, district Durg, Chattisgarh (1977-1993);

The struggle of contractual workers in the private auxiliaries and ancillaries of the Bhilai Steel Plant for unionization, recognition as direct employees, and the implementation of labour laws (1990-2016);

The struggle of the contract workers in the Jamul Cement Works of the private sector cement plant ACC Limited (now Holcim/ Adani) for regularisation (1990–2016).

In all three cases, despite the fact that contractual workers carried out permanent, perennial work in core production for even decades together, the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970 (henceforth CLRA Act) could not come to their rescue.

This experience prodded me to try to understand how, despite the legislative intent and potential; the framing, execution and legal interpretations of the CLRA Act have not only failed to abolish contract labour, but have actually legitimised its existence to the extent that today a new legal framework is coming into existence, where contract labour is no longer recognized as an evil and in fact it is the regular, permanent workman that has been abolished. The study of this Act is divided, therefore, into five parts:

A: The bulk of this paper is the history of the passage of the CLRA Act, pre-legislation procedures, situation on the ground at the time, and the political context of passage of the Act. It is a chronicle of a death foretold – the CLRA Act began with basic weaknesses which the trade unions vociferously pointed out, and which were to lead to its progressive weakening.

B: The working of the Act, particularly with reference to the abolition of contract labour by the routes of (i) notification, (ii) through the recommendation of the contract labour advisory boards. How successful or otherwise were these two routes? What was the effect of the 2001 SAIL judgment on the functioning of the contract labour advisory boards?

C: Lifting of the corporate veil, “sham and bogus” contract labour, and the role of the Industrial Courts in regularising contract workers.

D: Situation of contract labour over time – Increasing Contractualisation and Increasing gap between the wages and amenities of Permanent and Contractual Workers – findings of an Unpublished Survey in the Cement Sector.

E: Case study of the struggle of the contract workers of ACC Jamul for regularisation.

Methodology:

This paper is based on the following sources:-

Documents relating to Parliamentary Debates, and Proceedings and Report of the Joint Parliamentary Committee formed prior to the passage of the CLRA Act.

Case laws of the Supreme Court and High Courts relating to the abolition of contract labour and the functioning of the CLRA Act.

Discussions with a few trade union leaders and labour experts. Particularly for the discussion regarding the functioning of the Central Advisory Board, I am indebted to Shri Vivek Monterio of the Central Trade Union CITU who shared with me his experience as a member of the Central Contract Labour Advisory Board from 2001 to 2018, and also many relevant documents placed before the Board.

Personal experiences of the struggles for the regularisation of contract labour particularly of contractual workers of the Jamul Cement Works of the ACC Cement Company, organised by the Pragatisheel Cement Shramik Sangh.

PART A: The history of the CLRA Act

I studied pre-legislation processes in some detail, particularly – the evidence adduced before the Joint Parliamentary Committee set up to review the CLRA Bill (henceforth JPC); the Report of the JPC and the Minutes of the Dissenters; and the Rajya Sabha Debate prior to the formation of the JPC. I discovered, what were for me, many somewhat counterintuitive facts about the situation of labour in 1968-69:

In many government or public sector run establishments – railways, ports and docks, mines, and public sector steel plants – by that time, already a large proportion of the workforce were contract workers. The same was true of new under-construction development projects.

However, labour unions still had considerable political clout at that time. They were well represented in the Parliamentary debate, cutting across regions and political parties; as well as before the JPC, which on their invitation actually visited various sites all over the country where there were large numbers of contract workers. These unions, though usually of permanent workmen, were certainly invested in the abolition of contract labour. All of them demanded that the CLRA Act should be an Act for Abolition alone, and claimed that in its present form emphasising regulation, the Act would only legitimize the existence of contract labour. All of them forcefully stated that the beginning should be made with the government/ public sector establishments abolishing contract labour.

The process of legislation on this issue concerning the poorest of industrial/ organised sector workers, though taking three years, was far more detailed and transparent than anything we see today, with recording of evidence, field visits etc. The facts gleaned from the field visits and representations by workers during the field visits were used by the Committee members to pose hard-hitting questions to the employers. The recently passed Labour Codes, on the other hand, were pushed through Parliament during a pandemic with little debate, with no consultation with trade unions, and certainly no analysis of data or field visits.

In the evidence recorded before the JPC, surprisingly, the government/ public sector employers/management staunchly defended contract labour and suggested that the abolition of contract labour was impractical. Their opinion clearly held much more weight than that of the private employers who were, of course, all for contract labour.

It appears that it was the strong stand of the judiciary in “The Standard Vacuum Refining Vs Its Workers & Others” in favour of contract workers that was one of the bulwarks of the argument for abolition. Interestingly the role of the judiciary after the coming into existence of the Act became increasingly ambivalent and ended in outright hostility to contract labour in 2001 with the “Steel Authority of India & Ors Vs National Union of Waterfront Workers & Ors” matter.

Parliamentary Debate

The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Bill, 1967 was placed in the Lok Sabha on 31st July 1967. Almost 9 months later, on 7th May 1968, a Joint Committee was proposed by the then Minister for Labour and Rehabilitation – Mr Jaisukhlal Hathi – in the Lok Sabha, which motion was adopted by the House.

When the same proposal came up for endorsement in the Rajya Sabha, several members interjected forcefully. The following excerpts from the debate show, not only that, by this time industries such as plantations, mines, agro-based industries like sugar industries, and ginning mills of the textile industry were already using high proportions of contract labour; but also that, on the other hand, a strong opinion in favour of its abolition existed, cutting across regions and political parties. Shri Rajnarayan (Samyukta Socialist Party) also spoke in the course of the debate of how contractors were flooding the poorer districts of Mirzapur, Azamgarh, Devaria, Gorakhpur, Basti etc (of Uttar Pradesh) and herding together poor persons to work as contract labour on major development project programmes. From the speech of Shri Venkatraman (Congress), it also appears that in certain areas there were strong movements for abolition of contract labour in South India which were being kept at bay by promising that a beneficial legislation was on the anvil and the government was in the process of passing it. This speaks to a different political culture, largely sympathetic to the plight of the working class, prevailing among the elected representatives at the time.

“SHRI ARJUN ARORA (Uttar Pradesh)(Congress): Madam, I support the motion, but I feel it is a highly belated measure. It should have been brought long ago. And it is also a half-hearted measure. Contract labour has been the curse of Indian labour, the biggest curse of Indian labour, and as early as 1931, the Royal Commission on Labour in India recommended its complete abolition. It is really ironical to find that what the Royal Commission recommended in 1931 was not done by the Royal Government till 1947 and our Government, the people’s Government, has also taken 21 years to bring forward a Bill for abolition of contract labour….

….. If you abolish anything, you do not have to regulate it. The very fact that this Bill seeks to regulate contract labour under certain circumstances implies that it is not going to abolish it. I wish the Bill was primarily aimed at abolition of contract labour and no regulation whatsoever would then have been necessary. What happens today is that contractors are fattening themselves at the expense of what is called contract labour. There is no security of employment for labour employed by contractors. There is no mechanism for the enforcement of labour laws on labour employed by contractors. … There is no provision and no arrangement for giving contract labour fair wages or reasonable wages. There is not even any arrangement of regular payment of wages to contract labour. All possible ills concerning labour which were prevalent in the 19th century, before the first Factories Act came in 1881 or so, are still prevalent in the country as far as contract labour is concerned. I am sorry the Minister has not thought it proper to bring forward a Bill for complete abolition of contract labour, but has sought only to regularise their condition of work. Even as far as regulation of contract labour is concerned, the Bill does not make adequate provisions; it does not make provisions which may be in line with the Factories Act or other labour legislations in force in the country. I hope the Select Committee will take care of all these things and a better Bill, a more determined Bill, a fairer Bill will emerge out of the Select Committee.”

“SHRI BALACHANDRA MENON (Kerala), (Communist Party of India): Madam Deputy Chairman, I have only two suggestions to make. This Bill is only giving a statutory basis for contract labour. For the past few years we have seen too many employers and estate owners switching over to contract labour, even in regard to work of a permanent character. For example, in plantations in spite of the fact that productivity has increased and production has increased, in spite of the fact that larger areas are coming under plantation crops, the total number of workers remains the same as before. That is because most of the work is being handed over to contract labour, even work of a permanent character. … Every time a new legislation comes, every time the worker gets a higher wage or bonus or some other benefit in the shape of gratuity, etc., the employers try to escape these things by creating labour which will always be on a contract basis. So, I would suggest that we should insist that for every work of a permanent character no employer will be allowed to hand it over to any contractor. … We know, for instance, that there are hundreds of workers employed in the bidi industry. The attempt is to subdivide the bidi factories under independent employers who are really contractors. Legally he is an independent employer because he has the licence but he gets only a commission from the main employer. In such cases we will have to see whether the product is for the main employer and, if so, such work should not be deemed to be under any contract. I would, therefore, suggest that all these things will have to be looked into by the Joint Select Committee.”

(We see that this is still a period when bidis were still rolled in factories, today they are almost universally manufactured through a “putting out system” involving entire families, particularly women and children, at a pittance of a wage. The “Beedi and Cigar Workers Act, …….” which was brought about to rectify this, which has also not been effectively implemented, is also on the verge of repeal with the coming into force of the OSH Code 2020. Again there are no provisions either in the OSH Code or in any other Labour Code commensurate with the provisions of this Act.)

“SHRI A. G. KULKARNI (Maharashtra) (Congress): Madam, I am lending my support to the Hon. Member, Shri Arjun Arora, that this Bill is a half-hearted measure in bringing about some improvement in the contract labour. Madam, you are well aware that in industries, particularly agro-based industries, in the working season, a majority of the sugar factories employ around 4 thousand workers. Out of that number, 3 thousand workers are contract labour mainly employed for harvesting and post-agriculture purposes. Madam, this labour is not given even the minimum wage; it is given a wage which is very substandard. So, actually the Government should have come forward with a measure for the abolition of contract labour because it does not get any justice at all, and this happens usually in the case of nearly three-fourths of the workers employed in some such industry where the employment is on a large scale. …… Madam, again this happens in the rural areas and in the villages where cotton and groundnuts are processed in the factories. The big employers in the ginning and other factories give all this work to them in order to avoid or escape the clutches of the Industrial Disputes Act or the Factories Act or some other Act. They give all this work in a piecemeal fashion to the various contractors and though the employees are old and are responsible to them, they are being fraudulently shown as employees of the subcontractor and thereby the labourers and the employees of the contractor do not get whatever rightful wages they are expected to get. In this connection I would urge upon the Select Committee that there should actually have been the abolition of contract labour and not such half-hearted measures like this for improving their emoluments.”

“SHRI M. R. VENKATA RAMAN (Madras) (Congress): Madam, I would request that this matter be dealt with extremely urgently and even set a time-limit for the report of this Committee to come before the House for discussion. Madam, every time this issue has come, the workers have been told that the matter is before Parliament…….. I happen to be the President of a trade union in Tamilnad where there are 10 thousand workers working in the mines in Salem District. Madam, 7 thousand of them are on contract labour, although the 7 thousand and 3 thousand do identical work. By keeping them on contract or as contract labour the employer does not have the obligation of provident fund or insurance or bonus and all the other things which go with permanent employment. This is a very vexed question. The companies are running very profitably in that particular business of manufacture of firebricks etc. They say that the matter is pending before Parliament and Parliament is going to pass a statute on contract labour and under these circumstances how can they abolish contract labour immediately? With great difficulty the matter has been referred to a Tribunal along with other issues but I cannot wait indefinitely like this. And rightly the State Government says that mines are under the Central Government and thus they do not bother about what happens. So, while agreeing with the sentiments expressed by Mr. Kulkarni and the points made by Mr. Arora and Mr. Balachandra Menon, I would urge upon the Minister that further delay in this matter is absolutely pointless and the Hon. Minister must give top priority to this matter.”

“SHRI JAISUKHLAL HATHI (Minister for Labour): – So far as the expeditious consideration of the Bill is concerned the motion says the Committee shall report by the first day of the next Session. So, this is the time given for the Committee for its deliberations. So far as the other point is concerned, the Bill is for progressive abolition of contract labour. It was discussed by the Tripartite body and it was found that it may not be possible to abolish all the contract labour at once. There might be some casual labour as the Member himself has said. A distinction has to be made between casual work and work of a permanent nature. In work of a permanent nature, no contract labour could be there and that should be abolished but where the work is of a casual nature, this may be allowed but there also various safeguards have been provided like giving licence, registration, and then certain conditions like the principal employer will be liable for the wages and several other conditions also have been laid down. All these matters are there but if there is any other suggestion to be made, naturally I am sure the Joint Committee will consider it.”

The Joint Parliamentary Committee

The 45 member Joint Parliamentary Committee (henceforth JPC) also seems to have been very serious about its work. The Committee itself had a varied composition including both those who were pointedly in favour of labour and those who were in favour of the employers. But the overall inclination of the JPC was more sympathetic to the workmen. The itinerary of the Committee described in their own words was as follows:

“5. The Committee held thirteen sittings in all.

6. The first sitting of the Committee was held on the 14th May, 1968 to draw up their programme of work. The Committee at this sitting decided to hear evidence from public bodies, trade unions, organisations, associations and individuals desirous of presenting their views before the Committee and to issue a Press Communique ‘inviting memoranda for the purpose. The Committee also decided to invite the views of some All-India representative trade unions central organisations, railway trade unions federations, Railways, C.P.W.D., Ports and Docks, Coal and Steel undertakings and all the State Governments/ Union Territories on the provisions of the Bill and to inform them that they could also give oral evidence before the Committee, if they so desired.

7. 33 memoranda/ representations on the Bill were received by the Committee from different States/ Government Departments/ associations/individuals. (Appendix III).

8. At their third sitting held on the 21st June, 1968, the Committee decided to undertake on-the-spot study visits to the different regions of the country where contract labour was employed in large strength to enable them to acquire first-hand knowledge of the conditions in which the contract labour worked.

9. At their fifth sitting held on the 27th August, 1968, the Committee decided to divide themselves into four Study Groups for the purpose of undertaking an on-the-spot study and approved the tour programmes of the Study Groups to visit the various industries, Ports, Docks, Railway Establishments etc. in the States of West Bengal and Bihar; Maharashtra and Goa; Mysore and Madras and Andhra Pradesh and Orissa during September/ October, 1968. (Appendix IV). During their visit, the members saw the working conditions of the contract labour and held discussions with the various officials and representatives of non-official organisations on the provisions of the Bill.

10. The Committee has decided that the Study Notes on the visits undertaken by their Study Groups should be laid on the Tables of both the Houses.

11. At their second, fourth and sixth to ninth sittings held on the 20th and 22nd June, 26th to 28th September and 23rd November, 1968, respectively, the Committee heard the evidence given by 12 parties. (Appendix V).

12. The Committee have decided that the evidence given before them should be printed and laid on the Tables of both the Houses.

13. The Report of the Committee was to be presented by the first day of the Fifth Session of Lok Sabha. As this could not be done, the Committee at their second sitting held on the 20th June, 1968 decided to ask for extension of time for presentation of their Report up to the first day of the second week of the Sixth Session. Necessary motion was brought before the House and adopted on the 22nd July, 1968. The Committee decided to ask for further extension of time up to the last day of the second week of the Seventh Session which was granted by the House on the 18th November, 1968.

14. The Committee considered the Bill clause-by-clause at their tenth to twelfth sittings held from the 6th to 8th January, 1969.

15. The Committee considered and adopted their Report on the 29th January, 1969.”

Among the 33 Memoranda received by the Joint Parliamentary Committee, there were:

Memoranda of Governments – Assam, Haryana, Pondicherry, Delhi Administration, West Bengal, Government of Goa, Daman and Diu, Madhya Pradesh.

Memoranda of representatives of workers – Indian National Trade Union Congress, Lucknow (evidence recorded); Dakshin Railway Employees Union, Tiruchy (evidence recorded); All India Trade Union Congress, New Delhi (evidence recorded); United Trade Union Congress, Calcutta; Dakshin Railway Employees Union, Madurai; All India Railwaymen’s Federation, New Delhi (evidence recorded); National Federation of Indian Railwaymen, New Delhi (evidence recorded); Hind Mazdoor Sabha, Bombay (evidence recorded); Hindustan Lever Mazdoor Sabha, Calcutta; Railway Go-downs Workers Union, Howrah; Garden Reach Workshops Mazdoor and Staff Union, Calcutta; National Union of Waterfront Workers, Calcutta.

Memoranda of representatives of private employers – Hindustan Lever Limited, Bombay; All India Manufacturers Organisation, Bombay (evidence recorded); Employers Federation of India, Bombay (evidence recorded); All India Organisation of Industrial Employers, New Delhi (evidence recorded); Calcutta Tea Merchants Association, Calcutta (evidence recorded); Builders Association of India, Bombay; United Planters Association of Southern India, Coonoor; Calcutta Tea Traders Association, Calcutta.

Memoranda of representatives of government organisations – Bombay Port Trust, Bombay; Ministry of Railways (Railway Board) (evidence recorded); Central Public Works Department, New Delhi (evidence recorded); Hindustan Steel Limited, Ranchi; Madras Port Trust, Madras; Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation, Calcutta. (The evidence of the Minerals and Metals Trading Corporation of India was also recorded although no Memorandum was submitted by them.)

The four Study Groups formed by the JPC visited the following establishments and organisations:

Study Group I (West Bengal and Bihar): –

(Private Sector): Tea Houses and Transit September Sheds, Kidderpore Dock Area, Calcutta; Hindustan Lever Ltd., Garden Reach, Calcutta; Balur Scrap Yard, Howrah; Banksmullia Colliery, Asansol;

(Public Sector): Calcutta Electric Supply Company, Southern Branch, Calcutta; Railway Loco Shed, Howrah; Goods & Parcel Sheds, Howrah; Garden Reach Jetty, Calcutta; Garden Reach Workshops, Calcutta; Port Commissioners Office, Calcutta; Durgapur Steel Plant, Durgapur; Hindustan Cables Ltd., Chittaranjan; Chittaranjan Locomotives, Chittaranjan; Bokaro Steel Plant, Bokaro; Hindustan Steel Construction Corporation, Ranchi; National Coal Development Corporation, Ranchi; Heavy Engineering Corporation, Ranchi.

Study Group II (Maharashtra and Goa) :–

(Private Sector) Bidi Manufacturing Unit Factories, Camptee (Distt. Nagpur); Gumgaon Manganese Mines, Khapa; Carnac Bunder Goods Shed; Bombay; Mechanical Ore Handling Plant of M/s Chowgule and Co. (P) Ltd. Marmugao.

(Public Sector) Maharashtra Housing Board Construction Site, Bandra, Bombay; Bombay Port Trust, Bombay; Mazagaon Dock Ltd., Bombay; Bandra Loco Shed, Bombay; Iron Ore Mines, Hicholim (Goa); Marmugao Harbor, Marmugao (Goa).

Study Group III (Mysore and Madras) :–

(Private Sector) Dalmia Magnesite Corporation, Salem; Beedi Factories, Mangalore; Bondel Quarry Mangalore.

(Public Sector) Hydro-Electric Project, Sharavathi; Railway Coal Handling Work at Bangalore City Railway Station; Railway Coal Handling Work Basin Bridge, Madras; Madras Port Trust, Madras; Mangalore Harbour Project; Mangalore Bunder; Construction site of new Mangalore— Hasson Railway Line.

Study Group IV (Andhra Pradesh & Odisha): –

(Private Sector) Hyderabad Allwyn Metal Works Ltd. Hyderabad; Hyderabad Asbestos Cement Ltd. Hyderabad; Associated Cement Company Ltd., Kittna Cements, Tadepalle; Andhra Cement Company, Vijayawada; Caltex Oil Refineries (India) Ltd., Vishakhapatnam; Orient Paper Mills, Brajranajgar, Orissa.

(Public Sector) Construction site of new Administration Block of South-Central Railway, Hyderabad; Hindustan Shipyard Ltd., Vishakhapatnam; Vishakhapatnam Port; Rourkela Steel Plant, Rourkela.

I have not been able to access the Study Notes or copies of the original Memoranda, particularly of the various governments, all of which would be very useful to u nderstand the situation of contract labour, as well as the stated stand of the governments at that time. The evidence recorded however is available and a study of this shows the following:

Evidence adduced by the workers organisations:-

I have quoted the evidence given by the workers organisations at length below. The reason is that the following interesting facts emerge from their evidence:

The Unions, across parties and industries, generally representatives of the regular workers were extremely anxious about growing numbers of contract labour, particularly in the government and developmental sector.

They were unanimous that the Act should address abolition alone, that regulation was not feasible or enforceable, and if at all it was to be effective, it should address the primary issue of wage parity and also benefit parity with regular workers.

They were also unanimous that abolition should begin with the government, they saw the government as the largest employer and also the largest violator. Thus, for them, the government was not in the role of a neutral umpire between employers and workers.

Naturally, in those circumstances, they were wary of giving Governments the power of notification or exemptions. And they also felt that between the Government and the employers, these parties would have the majority in the Advisory Boards. Hence the request for giving these powers only to a judicial authority.

Concern was repeatedly expressed that the contract workers were given no direct forum for redressal of grievances, including for wages, for instance under the Payment of Wages Act.

The Unions wanted the four criteria for abolition of contract labour stated in the Standard Vacuum Case, namely – work of permanent and perennial nature, work necessary and incidental to the particular enterprise, work sufficient to employ regular workmen, and work which was normally done in other enterprises by regular workmen – to be specifically included in the statute and not merely as criteria for consideration by the Advisory Boards.

(Here it is important to recall that in the Standard Vacuum Case, the case was filed by regular workers on behalf of contract workers, who did not even qualify as ‘workmen’ at that time, and the judgment, most remarkably, holding that the regular workers had a ‘community of interest’ with the contract workers, not only held the dispute as maintainable, but decided it in their favour. But after the CLRA Act clearly demarcated the two categories of workers, the option of regular workers representing the contract workers was also ousted.)

The Unions all expressed concern at a minimum of 20 employees being made necessary for applicability, as they all felt that it would become very easy to avoid application of the Act using sub-contracting. (The new Codes have increased this number to 50.)

The concerns of the Unions proved prophetic. The remarks in italics are mine.

Shri PK Sharma of the INTUC made several important points. The only Committee member who questioned him persistently on behalf of the employers was Shri RK Amin. Almost all other members used him as a sounding board as to which provisions of the Act would be effective, enforceable etc and encouraged him to elaborate his views. The following were his views in brief:

”If the government is clear that the contract system should be done away with then it should specify that, under no conditions will contract work be allowed in any industry so far as the principal processes of the industry are concerned.

The contract system should be abolished altogether and then the advisory boards can advise the State Governments to exempt certain processes.

In the State tripartite committee meetings held all over India, they had unanimously requested the Central Government to abolish the contract system. (Note that the Labour Minister had, on the contrary, claimed that in the Tripartite meetings it was concluded that a blanket would not be practicable.) But when the Central Government has come forward with this Bill, we find that they only express a fond hope, and delegate the power to abolish to the State Governments implying thereby that this is an evil which they shirk to abolish, and which they want the State Governments to abolish.

This Bill emanates from the Government of India and from Parliament; at least in the public undertakings directly under the Central Government, could not this Bill abolish outright contract labour? If such a provision had been made in this Bill, could it not have been easily implemented, to start with? This Bill says that an attempt will be made to abolish contract labour gradually. Could not such a gradual attempt have been made right in the public undertakings?

The clause V(a) should be amended so as to cover seasonal work so that dal mills, rice mills, sugar industries and all industries of seasonal character are covered.

Unless the contract between the principal employer and the contractor specifies that the lowest wage payable should be the same as is prevailing in the industry, it will not be able to check the low wages of contract workers.

Loading and unloading is a continuous process and it should not be considered as an irregular or intermittent process.

Regarding penal provisions, I have already suggested that these should be made a cognisable offence and the proceedings should be initiated on the application made by the Trade Union or the workman who has suffered.”

Shri KG Shrivastava of the All India Trade Union Congress:

“One of the characteristic features of the pattern of employment in the Iron Ore Mining Industry is the employment of contract labour even for regular jobs of the various mining operations. The Labour Investigation Committee has observed that the system has led to serious abuses of which underpayment of wages, miserable housing, sweating conditions of work, disregard of the provisions of the labour laws are the chief. The Committee opined that the legal abolition of the contract system would improve the lot of the workers. At the time of the present survey it is estimated that in the country as a whole, nearly 56 per cent of the mines employed such workers. (The contractual miners in the captive iron ore mines of the Bhilai Steel Plant, a public sector steel plant among whom Shankar Guha Niyogi worked are a case in point here.)

Contract labour should not be engaged in the types of to work referred to in the Supreme Court judgment (Standard Vacuum Refining Co. of India Ltd. vs Their workmen and another) on this subject, namely, factories where: (a) the work is perennial and must go on from day to day; (b) the work is incidental and necessary for the work of the factory; (c) the work is sufficient to employ a considerable number of whole-time workmen; and (d) the work is being done in most concerns through regular workmen.

The Bill does not abolish contract labour at all. We demand that it should be abolished totally. Even the present strength of the inspectorate is such that they are not able to carry out the inspection of these labour laws. Even the Government has admitted that they are short of staff. (Where is the much-touted Inspector Raj?) Nothing will practically happen if this Bill is made into law.

We say no licence is necessary, it should be totally abolished.

The whole working-class movement is for the total abolition of this contract system. But when we discussed it in the Indian Labour Conference, it was brought to our notice by the then Labour Minister that it will not be possible with the present Constitution of India and unless amendments are made there to abolish it totally. (This does not seem to be a correct interpretation.) Therefore, a beginning has to be made …. so that it can be abolished at least in those categories in respect of which the Supreme Court has given a judgment. For the remaining part, our submission is that the principal employer should be made responsible to give them the same wages, same welfare facilities and the same working hours so that in practice they will come to the conclusion that employment of contract labour is not useful to them.

It has been our stand that in the railways and such other public sector undertakings work should be done departmentally and not through contractors.

Casual people are of a different nature; they are not contract labour as such. Our stand has been that casual employment should not be continued for a long time. There should be a specific period and we have achieved that, as far as Government departments are concerned. There, those who work more than six months should be given the rights of regular temporary employees. (We can see how in the Umadevi case the Supreme Court considered cases of casual labour employed for more than a decade and grudgingly allowed only a one-time regularisation for them, specifying that it would not act as a precedent to others.)

The penal provisions are never adequate in the labour laws. In many cases employers find it better to violate the laws and pay the penalty than to observe the laws.

As far as the provisions of this Bill are concerned, it does not aim at abolition at all; it aims at giving licences to these contractors.

It was felt that we would not be able to do without zamindars. We find now that we can do without zamindars. The same will apply to contract labour also.

Wherever there is work, irrespective of boundaries, people go in search of work. Suppose you set up a factory in Bhilai or Rourkela, people roundabout those areas do come, irrespective of State boundaries. It is not that they can come only through contractors. (When asked how people could be recruited without contractors.)

The limit on the number of persons in an establishment, may, in our view, be reduced to 10 because in some of the departmental undertakings, in canteens, etc. nearly always ten persons or one or two this way or that are employed.

The cost will go up as far as fringe benefits are concerned because the workers are denied these benefits. If they are employed directly by the Government these benefits will have to be given to them. To that extent, the cost may go up. But to offset this there is another side. The contractors take up the work at 100 per cent or 200 or 300 per cent above the real estimated cost.”

There were several representatives of railway workers and it is clear that contract and casual workers were being deployed in a big way in the Railways which was one of the earliest employment generating departments.

Shri V Sundarmurthy of the Dakshin Railway Employees Union, Golden Rock, Tiruchy had this to say:

“The railways are the main Government agency to enter into construction contracts throughout the railway system. The work relates to construction of bridges, new lines etc., remodelling, earthen work etc. Materials such as rails, steel, and cement etc. are supplied by the railways and the labour alone is supplied by the contractor. The contractor gets the labour mostly from the tribal people in the villages, who are most depressed and backward, and who are also mostly Harijans. The labour is not paid any standard wages only substandard wages are paid to the labourers. Moreover, the contractor is exploiting the workmen. There is no labour law followed. The Workmen’s Compensation Act, the Industrial Disputes Act and other labour laws do not apply to them at all. The contractor can terminate their services at his whims and fancies.

Secondly, even for works of a permanent nature, the contract labour system is followed in the railways. For instance, in the refreshment rooms, the catering department, the PW works, repairs to buildings etc. they are employing casual labourers and paying them sub-standard rates. In the transhipment yard also, casual labourers are employed. These are works of a permanent nature. Coal transportation, fuelling of engines, repairs to buildings, roads etc. are also permanent types of work. In order to reduce the expenditure and to implement strict economy, perhaps, they are following the system. Otherwise, there is no justification for bringing casual labour into these jobs. The Central Pay Commission has classified the nature of the work and also prescribed a particular rate for the work. And yet to deprive the workers of these benefits, this kind of system is being followed in the railways. Contract labour is employed in an indirect way in the loco-sheds etc.

They are engaged in loading and unloading coal fuel to engines, transhipment of wagons; repairs of roads, buildings, etc. They do similar work as the Class IV employees of the Railway.

I admit that the cost of production may go up, but what about the welfare of society and the uplift of our workmen?”

Shri JP Chaubey, Treasurer, All India Railwaymen’s Federation, New Delhi:

“The Railwaymen’s Federation is most concerned about the employment of 3 lakhs casual labourers in the Indian Railways. Their conditions are miserable. There is no protection for them. A lot of corruption is also going on in the employment of casual labour. Recently, the system of employment of casual labour is being expanded and many of the works which are of a permanent nature, in those works also, the railways are employing casual labour. Now, Sir, in a country where we want to establish socialism, this type of exploitation of labourers should be stopped. ……

This Bill which is under consideration, in fact, does not give any protection. The law should be positive and effective, all the provisions should be such that the workmen as also the trade unions can use them for the protection of the employees. Otherwise there is not going to be any sort of social security to these employees.

All those works which are of a permanent nature should be done by the railwaymen in service. The entire lot of casual labour should be treated as railway employees and they should be given all the securities which are guaranteed to an employee under the Constitution.

There should be a Judicial body appointed whom they can approach. Our experience is that if the power is delegated to the Government, the Officer who is on the job will go on doing things in his own way. He will be guided more by certain methods. So, if there is some provision for interpretation by the Government and for enforcement by them, then that would not serve the purpose. Therefore, some judicial or an Independent tribunal should be appointed for interpreting the provisions of the Bill and for ensuring the implementation of the provisions of the Bill.

The idea is if the word ‘casual’ is not there then the benefit of this Act would not apply to the casual labourer. I have already said that those persons who are employed on commission are also doing permanent nature of work. For the catering work one man is getting commission; the other is a casual labourer and still the third is a permanent employee. All the three work for the year. So, the very system should be abolished and everyone should be treated as a railway employee. Our Union has not only moved in the matter but we have given a strike notice also.

The entire Committee should recommend to the Government that they must introduce this Bill in Parliament for abolishing casual and contract labour. We are building a society. It is obligatory on the part of the Government to ensure a minimum protection to those who are being exploited for years. Therefore, whatever may be the expenditure and whatever may be the labour that the Government may have to undertake, such a rule or law is of a necessity. If Government have to take over such a large employment of labour, then we should have some sort of an independent Corporation. Mr. Sen said that there should be some sort of a big society having some treasury rules and so on. They can employ the labourers and keep on sending them wherever the works demand.

I have said that protection should be given to every individual. If that is not possible, then at least the number could be reduced from 20 to 10 (for applicability). Suppose somebody says that he will run the entire administration more economically and with less expenditure (on a contract basis), would you agree to it? “

SHRI R. K. AMIN: That time may also come.

Shri Keshav H. Kulkarni, Joint General Secretary, NFIR and Member, INTUC Central Executive Committee:

“Railways are one major industry where a very large force of contract labour is employed— beyond 3 lakh -mainly in the occupation of handling of coal and goods and engineering works etc. … The National Federation of Indian Railwaymen, has been repeatedly demanding that the conditions of work of contract labour are really bad and this system should be abolished and from that point of view, Sir, as I have already noted in the memorandum, my organisation welcomes this Bill.

With this introduction I would like to say further that a lot of discussion has been taking place in various forums on the subject since, perhaps, for the last three or four years. Now, in the context of these discussions, this Bill, so far as my organisation is concerned, is not completely satisfactory. The object, as has been stated by this Bill is to regulate or abolish the system of contract labour. I have gone through the various provisions of this Bill, and I wonder if either of these purposes, whether the regulation or the abolition, is going to be achieved this way in which the various provisions have been framed.

As far as regulation is concerned, there are in Chapter IV certain provisions relating to welfare and other health amenities etc. … The subject was under discussion subsequently in the Standing Committee of the 19th session of the Indian Labour Conference, where their recommendation was very comprehensive. And actually, this recommendation was based on the judgment of the Supreme Court (Standard Vacuum) and besides various things had been laid down in that resolution. Take for example, the recommendation of the 19th Session relating to certain conditions regarding fixation of wages, holidays, question of overtime, question of rest etc. These are things which are very necessary to be mentioned categorically in this Bill. Our view is that so far as the regulation aspect is concerned, whatever provisions have been made, … they are too inadequate, looking to the problem and also in the background of the recommendations of the Indian Labour Conference.

(d) This is a matter about which sufficient consensus has developed in the country.

These are things which are capable of very precise definition. There is no question of any confusion or equivocalness so far as the four types of works enumerated by the Supreme Court are concerned and also the 19th Labour Session came to that conclusion. It has been laid down that we can demarcate these types of work which need not be executed by contractors.

(e) In other sections there is a repeated reference about the Government taking decisions in consultation with the advisory boards. We are afraid if these things are mixed up and there is only Central Advisory Board we may not be able to do adequate justice to the particular industry and therefore, actually the point was discussed at the Standing Labour Committee and the suggestion was made for different committees, but looking to the whole scheme of the Bill and the way these advisory boards are going to play vital part, Committees may be too inadequate and, therefore, at least so far as these major industries are concerned our view is that there should be separate advisory boards.

(f) Now, at the end of clause 10 there is an explanation which is very important. It says:

“if there should arise any question about a particular work being perennial or not then in that case the decision of the appropriate Government thereupon shall be final”, Here, I would only add that as you are going to form these advisory boards for the effective administration of this Act so whatever the decisions are going to be taken should be in consultation with the Advisory Board.

(g) Now, along with ‘incidental to’ we wish it should be ‘incidental to or connected with’ because there are different types of work for example, in the case of Railways loading of the coal— now coal handling may be incidental to railway work but maintenance work is not incidental but connected and a large force is engaged in the engineering contracts. Therefore, ‘incidental to and connected with’ will cover a major portion.

(h) Under clause 21 there are only certain responsibilities fixed on the principal employer. No doubt, it is according to the recommendations of the Tripartite Body. As I have already remarked this Section is not adequate to give protection to contract labour. Here, the only abuse which is checked is that of short payment and also some responsibility is thrown on the principal employer. … But the question is who is going to fix the wages. This question came up before the tripartite body and at that time it was said legislative measures for fixing standard wages should be taken. It is a very important question. This question of wages is more important than these welfare and health measures and, therefore, until and unless that provision is made this question of regulation will not be satisfactorily solved at all. Therefore, this standard wage fixation should be there.

(h) For example, take the case of railway contracts. The contract may be on the railway basis. But the railways do not run according to the States. For example, take the Jaipur division of the Western Railway. It runs through Punjab, Haryana, UP, Rajasthan. Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra etc. There are nearly seven States. The rules and orders issued in the different States may be different, and therefore it will make matters complicated. Taking into consideration all these factors we have suggested that these things should be specified in the Bill itself. Already, we have some guidelines laid down. For instance, in the Shops and Establishments Act, we have provided for the hours of work, the rest period, how the overtime payment should be regulated and so on. There is one thing, however, which I would like to mention, namely that whatever hours of work may be there should be at least uniform. …… Under clause 12(2) it may form a part of the contract But what I would suggest is that the hours of work, the payment rates, the rate of overtime payment, the rest period, how the rest period should be controlled and so on should not be provided for separately but should form a part of this legislation itself, as has been done in the case of the Shops and Establishments Act and other such legislations.

(i) Then I come to clause 26 which says that no court shall take cognizance of any offence under this Act except on a complaint made by or with the previous sanction in writing of the inspector. In my view, this is not a satisfactory provision. We have suggested already that there should be a provision similar to that under the Payment of Wages Act, under which there should be a separate authority for the purpose. The provision here should be similar to those under section 22 and section 15 of the Payment of Wages Act. Under the present provision, unless the inspector gives permission, there is no chance of the employee getting any relief at all or getting any of his grievances redressed. So, this particular provision should be modelled on the basis of section 22 of the Payment of Wages Act and there should also be an authority as appointed under section 15 of that Act.

(j) In spite of various laws that have been there, our standing complaint is that the implementation of the various labour laws especially in the departmental undertakings of Government has been very indifferent, and very much halting too. We have repeatedly brought these things to the notice of the Administration. There is the question of these departmental undertakings exempting themselves from the various provisions of the labour legislation. Every year, the Labour Ministry publishes reports about the administration in the working of the Employment Regulations, The Workmen’s Compensation Act, the Payment of Wages Act etc. in the railways. Every year, the Labour Ministry quotes a number of cases where particular provisions have not been followed and have been violated; the next report only contains information to the effect that so many irregularities were found and they were brought to the notice of the Administration, so many of them had been rectified, so many were under review and so many were under processing.

That is all that happens. Is this the way the Government would have dealt with an employer if he had violated a law, if he were a private employer? The whole difficulty is because the question of delicacy between sister departments comes into the picture, and whatever legal protection would be there for the workers to secure the benefits under particular laws is not there in these Government undertakings. We are afraid that if clause 20 or clause 26 is allowed to remain in its present form, the same thing may happen, so far as these industries are concerned. Moreover, when we make a definite law where we confer certain rights on the employees, we should also provide that if the employee feels that a particular benefit has not been extended to him, he should have the right to seek remedy in a court of law in respect of redressal of the grievance that he has. Therefore, this clause should be totally changed and provision should be made for the appointment of an authority as under the Payment of Wages Act.”

Shri V.B. Kulkarni, Hind Mazdoor Sabha:

“My first point is that abolition of contract labour should be the aim of this Bill and not regulation of it. We believe that abolition would be easier than regulation of contract labour system. We also believe that contract labour system survives by exploitation of labour. Cheaper labour without any security of employment, without any retirement benefits, without any regulated working hours is the main sustaining power of this system. Since it is bad for administrative convenience and economic reasons it should not be continued.

It cannot be done overnight. Therefore, if the decision is in favour of abolition of contract system the residual remnants of this system should be placed under severe restrictions so as to make it a thoroughly unattractive proposition.

I say that abolition would be easier because smallness of the contractors will make it almost impossible for any active functioning and to make the law operative or enforceable. We have seen that in small industries even the most common and reasonable legislation like the Shops and Establishment Act is not being implemented.

If you come to the conclusion that the contract labour system in its totality should be abolished, then the government should first start abolishing it. They are the largest single employer and by all estimates they are having the largest force of contract labour in various departments. Since ours is a developing economy and since we spend 40 to 45 percent of our developmental expenditure on construction work and since we allow over 60 to 75 percent of our construction work to be done through contract labour, it is of the utmost importance that the government should show its sincerity and reasonableness towards labour by abolishing the contract labour system in its departments. Since development is going to be a perennial matter— there would be development even 50 or 100 years hence— there should be a regular department for construction work through which we can do away with the contract labour system in construction work.

The only argument that can be levelled against my suggestion would be economic costs and administrative difficulties. But to end the exploitation which exists today which one cannot describe adequately, the economic reasons and administrative difficulties do not go well with democratic system and the goal of the welfare state. Therefore, the government should be the first to start it. If the government starts it, then the private sector employers will have no grudge and no complaint. But if the government continues it and if the government asks the private sector to do away with it, there would be a great deal of opposition from the private sector employers.

However, if the Committee comes to the conclusion that contract labour cannot be abolished in certain spheres of our economic activity, then I would urge that this Committee should draft the Bill in such a way, by making amendments and putting severe restrictions, to make employment of contract labour thoroughly unattractive. To do so, the law must provide equality of wages and conditions of work in various categories of employment in various industries. No doubt, wages and conditions of work will differ from place to place and there cannot be any standardisation. I am not asking for standardisation. What I am saying is that the contract labour should get the same salaries and benefits which the regular employees are getting. They should not get a lesser wage. Contract labour is paid anything between 35 to 50 percent of what the regular employees are getting. They are not getting other benefits like holidays, retirement benefits, provident fund, gratuity and so on. If they are all provided in the Act, I am sure the contract labour system will die its own death.

Everything should be provided to them. Since the Government provides housing to their own employees and since they ask the private employers to do it, there is no reason why the contract labour should be denied these benefits.

Then I would suggest that the Bill should be enforced immediately and simultaneously at all places. No place should be left out of its scope, be it the State of Jammu and Kashmir or any other area. (Here the right-wing anger at the exclusion of Jammu & Kashmir with little appreciation for the reason for it is visible. Actually J & K had an extremely active trade union movement and most labour laws were immediately adopted and better implemented there!)

Then, I feel the limit of 20 is on the high side. We have seen a lot of industries, which have smaller unit factories employing one person less than 20 to get rid of the clutches of the various labour welfare legislation. So, the number should be reduced to 5, if it cannot be reduced to 1. It could be reduced to 1, provided government decide that contract labour is bad and should be abolished.

The largest single industry in the country is the construction industry, and in that industry a large number of women are employed. They are married and have children. They come to work with children. Many of you have seen, just as I have seen, their putting their children in baskets or tying them between the length of two trees or keeping them in the shed and going to work. This is inhuman. If this Bill is to provide any benefit, it should ensure that women workers engaged by the contractors get the benefit of creches and maternity benefit. Whatever facilities we give to women in other industries should be provided to them here also. There is no mention of it in the Bill. (In practice, it was to take at least three decades after this before construction labour got any protective laws.)

Surely, I would not like women employees to be employed because they are cheaper, because they do not ask for creches and dormitories for their children, because they do not ask for special privacy by way of washing rooms and other things. I would surely like women workers to be employed more and more but I would surely not like them to be employed under sub-human conditions.

Then, there are two words appearing in this Bill at two places or perhaps more. The words are “intermittent” and “casual”. I feel, unless these two words are qualified properly and adequately, they are likely to be misused and will leave open a lot of litigation. … I am told, in Railways 8 lakhs of the employees are casual and some of them retire as casuals. I also know of instances in the Bombay Naval Docks, where I know from personal knowledge, hundreds of employees retired as casuals in 1956 after years of service. What is casualness of employment? I would appeal to you, therefore, that the terms “intermittent” and “casual” should be specifically stated in the body of the Bill itself.

About the Central and State Advisory Boards, as the Bill stands at present, I am not prepared to make any distinction between the representation given to the Government and the employers because the Government is the largest single employer and they together against me as a worker form a majority. I am not casting any aspersions on the Government representatives, but the fact remains that numerically they are stronger than me. If they are stronger, they will make a mockery of the tripartite system or the advisory board. … So I strongly feel and I demand on behalf of my organisation .. that the workers should be given equal representation, that is, equal to the total number of Government nominees and the employers’ nominees, if this thing is to be permitted.

Then, in clause 15(2) of the Bill it is stated “as early as possible”. This is a beautifully vague statement. There must be some time limit. If this Bill is to go as it is, at least you will see that a time limit is specified. Within a reasonable period, the decision must be given; otherwise this vague term “as early as possible” has got no meaning. People will have to nominate their heirs and executioners to receive the benefit.

About the recovery of dues, it should be open to the employees to recover their dues either from the contractor or from the principal employer through a court of law through the Payment of Wages Act. Depending upon the situation they will either sue the contractor or the principal employer or both, but such a provision should be there in the Bill itself.

We would not like the right of adding to the Schedule the industries to be covered by the Bill to rest with the Government; in fact, we suggest that the Bill should stipulate that whether the industry is to be covered under the Act or not, and whether the work could be done through the contractor or not should be determined by a judicial body, be it a labour court or a tribunal. I would suggest a labour court because the tribunal would provide a forum for appeal, but it should not be left to the Government or the advisory Board, Central or State, to recommend which industry is to be added and which is not to be added.

Take for instance, the Minimum Wages Act. The Government has a right to add to the schedule the industries, and that right has been used by the Government in a very halting and half-hearted manner. Se it should not be left to the Government to add to the list of industries and to give exemption. Let it be judicially decided whether the contract labour system should be continued or not in a particular industry or project.

If the Committee recommends that it is not for the contract labour but feels that it (abolition) cannot be done overnight or in the shortest possible period, for the limited period, I will accept the four criteria. (The four criteria mentioned in the Standard Vacuum Case). I am not mentally prepared to accept the economic and administrative considerations as a cause for the continuation of the system.

According to our estimate, the contractor is, generally, given about 10 per cent of the amount involved in the work. But he earns much beyond that. Our estimate is that he earns between 15 to 25 per cent by giving inferior type of work about which the employer should worry. … It is entirely true that the employer encourages the contract system because it is cheaper for the employer also. It is hardly possible to make a distinction between an employer and a contractor whose motive is profit.

All Government Departments should abolish contract labour. I am not exempting any Departments including Defence. …. 3 months is good enough to implement it.

I would repeat that the Hind Mazdoor Sabha stands for total abolition of contract labour system, but it visualises the fact that it cannot be done overnight. During this period between abolition of contract labour system in certain employment areas and where it could be allowed for some time because it cannot be done away with, during that period the contract labour should be given equity benefit with the regular employees so that the worst features of the contract labour system could be removed.

In its present form, first of all, this Bill will not satisfy the labour. Secondly, the implementation will be halting, because the rights are reserved by the Government. On the advisory committees, the representatives of the employers as also of the Government are in majority. You will have a statute on the book which will not be implemented. Leave it to a judicial authority to determine whether contract labour system is necessary in a particular sphere of activity.”

Evidence of the employers

The evidence of both employers from the public sector and the private sector was heard by the Committee. Here I have extracted the evidence rendered by the Member of the Railway Board at length to show several things:

a) Repeatedly variable workload is stated as the main reason for employing contract labour. This understanding is as if the worker is employed only if he/ she is working for every minute of the 8 hour work day. In many kinds of permanent work, the work itself has a cyclic rhythm with varying intensity and there are natural breaks in the production process. Also, for any human being carrying out work, breaks in the work are a part of that work. To claim that this is not “full utilisation” of a worker is to make all work completely mechanical as work on a conveyor belt. (As powerfully depicted in the film “Modern Times”) This has actually been achieved in the auto industry where despite the high payment, it was the absolutely dehumanising and alienating micro management of a worker’s time (exactly 7.5 minutes for a drinking water break) that led to massive revolt among the workers of Maruti Suzuki at Manesar, Gurgaon.

b) There is also the argument that the contractors carry out very “specialised work” using “specialised tools”, in which case, the workers could be permanent workers of that particular contractor. But in reality, usually the contractor is a mere supplier of cheap labour for whom the Principal Employer need not provide benefits and whose job is too precarious for them to unionise or demand even the statutory minimum. Workers carrying out a specialised task should also be better paid as skilled labour, but contract labour is often not even paid the statutory minimum wage.

c) The understanding of what a contractor does has also subtly changed with time. The earlier understanding was that a contractor was a person who undertook to carry out a particular job for a particular price within a particular time for a Principal Employer. He was expected to have the materials, equipment and supervisory capacity to carry out such work. In fact in a situation where the materials, equipment and supervision were of the Principal Employer, the contract was considered to be a “sham and bogus” contract, a “paper arrangement”, a “smokescreen” or “camouflage”. In such situations, in a catena of cases, courts held that the workers were for all practical purposes the employees of the Principal Employer and were therefore regularised. Unfortunately the 2001 SAIL judgment, by holding that a contractor could also simply “supply labour for a particular work”, legitimised such sham and bogus contractors also.

d) Another aspect regarding which the public sector employers were vociferous was that the provision imposing liability on the Principal Employer for the non-payment or short payment of wages by the Contractor should be removed as being impractical. This has proved to be one of the most effectively used provisions of the CLRA Act and has ensured some degree of accountability of public sector employers.

e) The most shocking aspect of the depositions of the public sector employers, amongst which that of the most articulate has been extracted below, show that there is no acknowledgment whatsoever of the need of their being “a model employer” (as stressed in several Supreme Court judgments); of the fact that infrastructure projects were never supposed to be “profit making” ventures; and of the fact that the much vaunted “trickle-down” of development was always understood, in the then prevailing progressive post-colonial economics, to practically occur in the form of enhanced “purchasing power” through the disbursement of better wages. On the contrary this public sector employer refers to the unlimited availability of the unemployed, and the prevailing starvation wages in the rural economy to claim that even paying the reduced wage of a contract/ casual worker is a great favour that the public sector provides to the unemployed. Clearly the levels of casualisation and contractualisation in the Railways, even by that time, with lakhs of such workers working for decades together, were already way beyond what the management representatives were willing to admit. The lame theory that some contractors even provided the workers better wages or working conditions could not be buttressed by even a single example.

f) The deposition of Shri BC Ganguli, Member Railway Board before the Joint Parliamentary Committee is being given here almost in full, because it exemplifies the neo-liberal logic that was later going to completely dominate discourse in the 1990-91 era of liberalisation, globalisation and privatisation. There is clearly no philosophy of “socialism” or “welfare state” or “trickle down of development” to be seen here in the management of public sector enterprises!!

Evidence of Shri BC Ganguli, Member Railway Board before the Joint Parliamentary Committee including the then Labour Minister.

(a) “SHRI B.C. GANGULI: In the Railways there are some incidental jobs like goods and parcel handling, handling of coal with cranes to the various loco sheds and in some cases we are still doing manual loading of the tenders of locomotives. We sometimes employ contract labour there. These are all jobs which are of permanent nature but of variable load. These are three types of jobs which are of a permanent nature but are done by contract labour. If the workload were, as I said, of a perennial nature without variation from day-to-day, constant load, there would be a possibility of getting these jobs done by departmental labour. But what happens is that all these jobs which we have given to contractors are of intermittent nature and load varies from day to day.

LABOUR MINISTER: It may be possible to devise a method whereby permanent nature of work with variable load can be managed in large centres by certain nucleus staff.

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: This is all right in principle. It is not good to mix up the working of a departmental job with that of the contractor’s labour. Suppose you have kept 50 permanent men as nucleus and you also employ the contractor there for taking account of variable load. That man’s difficulty will be that he has no permanent load. The contractor also keeps a nucleus to carry on his work. This is not a practicable or workable proposition. He will have his agents and organisation and he must find some minimum job to pay for these things.”

(b)” For building bridges etc. specialised tools and plant and specialised type of labour is needed. The contractor can afford such things. He has got a job here today and tomorrow he may have it elsewhere, say at Haldia port for instance. He can utilise the tools and plant and specialised labour as he has various places to work. We had in the olden days thought that we could keep some specialised equipment with us like pneumatic air-locks, but we could not utilise them fully.

LABOUR MINISTER: There is National Project Construction Corporation. They can deploy their men in various types of work. Can the Railways think of some such thing?

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: We have already got this corporation which is now functioning, as contractor also in the Farrakka barrage. We have now got one such body which also finds it difficult to get full work. It won’t be possible to have a multiplicity of agencies.

LABOUR MINISTER: If a contractor can afford to have men and then go on from place to place for work, why can such a corporation not do it? Perhaps the argument may be that when there is no work, the contractor can discharge those people.

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: That is the main thing. The second thing is that you will not be able to attract temporary establishments to work for the Government because we have a lot of limitations – payment of bonus and things like that, also the pay scales.

LABOUR MINISTER: They are not limitations.

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: They are big limitations.

LABOUR MINISTER: I am talking from the workers’ point of view.

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: I am talking from the Government point of view. Government cannot go on adding staff like this.

MR. CHAIRMAN: Recently we had gone on tour to some places where we saw work connected with the railways also. I concede there are many works, according to you, of a temporary nature, lasting four or five months where a contractor is engaged and then afterwards, they have to be employed elsewhere. Have you got any idea of certain works which are of a permanent nature, occurring for the last many years, which you get done through contractors, where those workers are called contractor’s employees, with the result that they do not get proper facilities? Are there contractors who do work only for the railways and not for other people?

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: There are certain contractors who work on the railways, in the PWD, in the docks, harbours etc. and there are some others who work only on Railways. There are various types of contractors. As I have explained, there are two or three categories of work of a permanent nature but with a fluctuating workload where we have gone for the employment of contract labour. Let there be no impression going round that the railways are functioning with contractors. The railways do not. If you take our working expenses, 60 percent is accounted for by the wage bill of our men. That is our trouble today. If we had functioned on any other methods which had been adopted by the company railways in the olden days, today we would have been in a much better position. But our trouble is that we have got a very very large number of permanent labour. I see very little scope for railways to expand their permanent labour in their working.

MR. CHAIRMAN: How do the conditions of workers employed under contract system compare with those of the regular workers in the railways

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: It all varies from contractor to contractor. There are some contractors who, according to my personal opinion, do not look after labour as they should. There you can say that the condition of the labourers employed by the contractor is worse than the labourers engaged departmentally by the railways. But I have known of certain cases also where contractor labour is better off than railway labour.

SHRI DEVEN SEN: Cite an example.

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: The Hindustan Construction Co. Ltd.

SHRI DEVEN SEN: That is not connected with railways.

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: I am talking of a comparable contractor. Hindustan Construction Co. is an Indian contractor. We are trying to take an employer like the railways. That being so, you cannot take Nathu Ram or Magan Ram; that comparison will not be appropriate.

MR. CHAIRMAN: The question is how these conditions compare between the contract labour and the regular labour? I am referring to the contractor who employs labour only for the railway purposes and he is employed by the railway contractor.

SHRI B. C. GANGULI: The railway departmental labour has got a timescale 70— 85, plus dearness allowance. Some private contractor may pay less because the Minimum Wage is less than that. When a contractor is a small man who takes a smaller contract, naturally he tries to limit his payment and the facilities to the barest minimum which is required under the law. He does not give facilities that the railways would give to permanent labour. The permanent labour in the railways has got medical facilities and housing facilities— not to the full extent of course. They are not available to an average contract labour.