Journalist cannot cover the labour beat without questioning extreme inequality- P Sainath

Workshop in Chennai initiates a much-needed critical dialogue about vanishing Labour Beat in the media landscape

One cannot cover the farming without challenging the big landlords, just like one cannot cover the labour without challenging the big capital. Without recognizing raising extreme inequality in the country

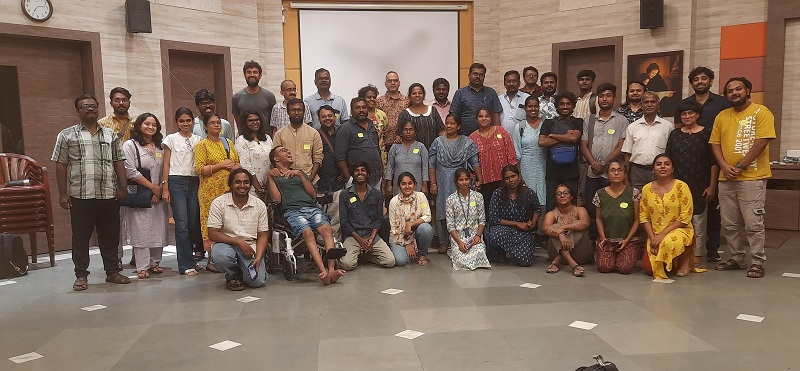

On Sunday, July 21, dozens of students, young journalists, activists, trade union leaders, and other sympathizers of the working-class movement gathered in Vidyasagar Hall, Kotturpuram, Chennai for a day-long workshop titled “Reclaiming the Space for Labour in Journalism: Beating Capital with Labour Beat”.

The Working Class consists of more than 50 crore of the Indian population, yet the journalistic space given to the stories that reflect the objective interests of the working class is vanishingly small in today’s media landscape.

Historically, there existed a dedicated ecosystem in the media, that covered such stories of interest to the Working Class. In the journalistic lexicon, it is called “Labour Beat”.

Given that this vanishing of labour beat from the media ecosystem is symbiotically related to the weakening of labour movement itself; a group of journalists, activists, and general sympathizers of the labour movement (in itself and its role in the overall democratization of the society) felt the need to have a closer look at the situation and brainstorming the way forward to nurture a newer generation of labour journalist equipped with newer tools available due to progress of technology. Thus arose the idea of this workshop.

In this report, we have documented various sessions of this workshop such as speeches on systematic erosion of labour beat, labour economy of Tamilnadu, ethics of Labour Journalism as well as hands-on interactive sessions on how to storyboard and methodology involved in making a video story. We also look at the various questions related to the demography of participants and accessibility of the venue, praises and criticisms from various sections, and reflect on the future possibilities.

This report emerged from our continuous engagement with the organizers over the weeks leading up to the program on Sunday and with our interactions with the persons from diverse backgrounds who participated in the program.

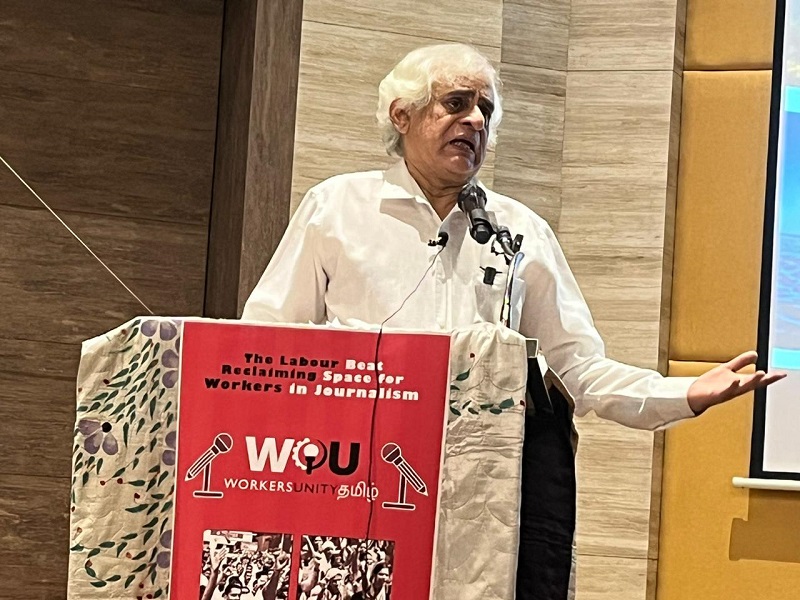

P Sainath’s Speech on the History of Labour Beat

Sainath in his speech covered how the media landscape (in terms of its class composition and its interest in the kind of stories it deems worthy) changed over the last few decades of economic liberalization and steadily increasing corporate monopoly over the media industry. He established his points with details of various publicly available statistical data.

He emphasized greatly the point that aspiring labour journalists must understand the context of change in the political economy and the rise of extreme inequality in the country in which they will be operating.

He started with his own experience of joining journalism nearly half a century ago and how things have changed since. At that time every established newspaper had a full-time labour correspondent.

In the early liberalization era of mid 90’s not a single newspaper had a full-time labour correspondent. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, the idea of dedicated labour beat itself started getting vanished and it essentially got merged into the industrial relation (IR) beat.

By 2005, there were essentially IR correspondents, who were basically communicating with the PR offices of the corporates.

It is ironic that such correspondents don’t have any actual contact with trade unions or the working class in general and they are essentially talking with industries to report about labour.

Sainath also emphasized that a number of other beats also essentially disappeared in the post-liberalization era. Around 15 years ago agricultural correspondents were basically communicating to agricultural ministers, not the people who make their livelihoods through farming.

Such agricultural ministers are so alienated from the actual farming process that they can’t even differentiate between two actual farm produce in practice. Today, such agricultural correspondents essentially talk to agribusinesses, not even govt officers in the agriculture departments.

No agricultural correspondent found it worthy to inform their readers about open official partnerships between certain agribusinesses and the Govt of India.

So, agribusinesses can now promote their products through official govt mechanisms. An aspiring journalist must understand this context and cover the stories through the lens of people.

Sainath also stressed that to cover a story genuinely from the people’s lens one needs to understand the labouring process first and need to challenge the persons holding the power positions. One cannot cover the farming without challenging the big landlords, just like one cannot cover the labour without challenging the big capital.

Sainath stressed about the rapidly rising inequality in India, especially after the liberalization in the nineties. He cited the work of the Inequality lab led by Thomas Piketty and his team which concluded that the wealth inequality in today’s India is greater than the heyday of British colonialism. Till 1991, India didn’t have any dollar billionaires, while the first dollar billionaire arose in 1996.

Today India has 240 dollar billionaires, which consists of only 0.000015% of the country’s total population, and has an accumulated wealth nearly equal to 29% entire country’s GDP.

Their accumulated wealth is greater than the country’s agricultural budget itself. Even among them, 30% of wealth is controlled by the top 5 richest person of the country. Such a massive accumulation of wealth didn’t come from nowhere, but it came from the exploitation and pauperization of crores of ordinary toiling masses.

He told how the Covid-19 pandemic served as a clear indicator to understand the process of wealth accumulation at the top of the economic pyramid by making crores of labouring people poorer. While crores of Indians were trying to sustain the bare minimum; in the first 12 months of the pandemic, India added 42 dollar billionaires, 24 of which are from the health sector.

Rapid concentration of wealth is reflected in the expenditure of electoral campaigns and as a consequence who gets elected. The number of Crorepati MPs grew from 53% in 2009 to 93% in 2024.

Thus nearly 500 crorepati today represent crores of Indians who are on bare survival. Thus it is not hard to understand why people’s issues like poverty and unemployment are not focussed by them. Sainath gave a rather interesting analogy for visualizing the actual mammoth scale of unemployment in today’s India. He said that, if one makes a queue of unemployed persons in India, with each unemployed person covering half a meter, the resulting queue will be more than 3 times the length of the entire coastline of India (even including the coastline of the islands).

He concluded with an explanation of why all these don’t get represented in the media today. Today’s media is essentially the media and entertainment industry controlled by big monopoly capital.

There is an ownership concentration of the registered media, with most registered media owned by a handful of corporates, each owning many at a time. It is practically impossible to raise any issue that is against the interest of the owners.

Sainath also stressed the fact that how change in class composition in the journalists resulted in the change in class concerns as a result of liberalisation. Historically, in the ’60s and ’70s most journalists used to come from the working class and lower middle-class background.

They were less “educated” in the traditional sense, but had an organic link from the class they were coming from. Gradually, as journalism turned more towards corporate PR & entertainment and a profitable business model around it arose, journalism training schools started popping up like business enterprises.

This created a generation of journalists totally alienated from the labouring people. One needs more journalists from the working-class background to change this situation.

Sainath also stressed that while the emergence of newer forms of digital alternative media has enabled the possibility of bypassing the censorship of anti-establishment news in the print and Television media, one must keep in mind that there is a possibility of even worse censorship coming on these alternate media through the algorithms and modern technologies.

However, there still exists some space for pro-labour reporting in alternate media and one must utilize it.

To watch the recorded version of Sainath’s Lecture the interested reader can go to the YouTube Channel WU Live or Workers’ Unity Tamil.

A highly important question regarding the status of unionization of journalists came up during the Q & A session following the talk. Sainath replied that instead of an increase in unionization, rather there has been steady de-unionisation. It is more likely that this is related to the changing class composition of journalists.

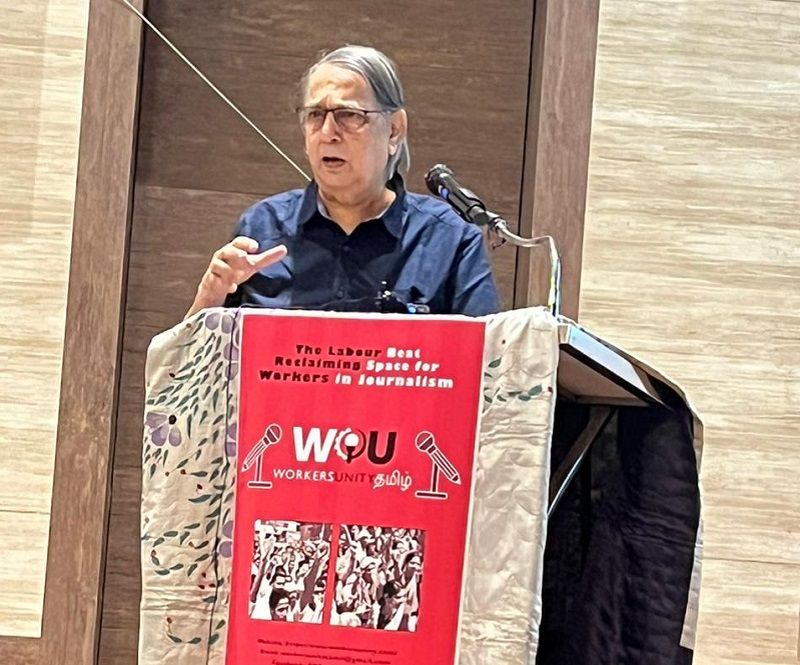

Vidyasagar’s Speech on Labour Economy of Tamilnadu:

In his speech titled “Labour Structure & Conditions in Tamilnadu”, Vidyasagar, with the backing of various govt and non-govt data, explained the overall patterns in India’s labour economy from liberalization onwards, as well as specificities of labour economy of Tamilnadu.

He identified how the trend of growth without employment generation and Capitalism’s increasing aggressiveness to negotiate in favour of capital is worsening the already dire situation of the working class in terms of wages, social security, workplace safety, fighting strength, and organizational capacity.

Post-1991 union govt’s policies too aligned with pro-capital, anti-labour tend.

As a result of the influx of capital, there is a general trend of exodus from agriculture. However, this exodus didn’t happen to manufacture. There is a growing service sector and more rural labour are entering it.

As a general trend, over the last 30 years, both industry and agriculture is loosing the capacity to absorb labour. Construction provided around 36% of jobs between 2000 and 2015.

Even in the high-growth industries employment generation is stagnant. Nearly 50% of the workforce in India still depends on agriculture. To increase employment generation and wages in agriculture more govt intervention is needed, but capital is forcing the other way.

While both in industry and agriculture the output has increased, wages have declined. In fact, export production has seen an inverse relationship with the labour standards.

Vidyasagar emphasized about decreasing of formal/regular employment and increasing contract labour along with decentralization of industries as a general trend in the neoliberal era. In fact, contract labour is employed more in capital-intensive industries like automobiles. The percentage of contract labour in the automobile sector increased from 11.6% in 2000 to 44.7% in 2011-12 and currently, it is nearly 60%. The gap in income levels between contractual and regular workers is increasing drastically.

He also mentioned various categories of informal labour like self-earning initiatives, working in family enterprises, in establishments, etc. Surprisingly, self-earning initiatives like street vendors, hawkers, etc, have increased to cover nearly 60% of the informal labour. At present 93% are informal workers, while formal workers only account for 7%. New labour codes will only increase this trend of contractualization and informalisation, and workers will lose their existing rights.

The fighting strength and collective bargaining capacity of the working class have decreased drastically. Despite the tremendous increase in number of workers from the 1980 level, the number of days of workers’ strikes has decreased significantly. Currently, there exist around a dozen Central Trade Union Federations, with nearly 60k registered unions. However, due to causes like the reserve army of labour, and low-paid contract workers, the organizational strength of the workers has weakened significantly.

Vidyasagar then focussed on the specificities of Tamilnadu (TN). TN, with consistently ranking among the highest in the country in terms of Gross State Domestic Product (GDSP), significantly contributes towards India’s overall economic growth. In TN, there are major industrial clusters like automobile, manufacturing, textile, electronics & pharmaceuticals. Chennai, the state capital is a prominent IT & business hub further bolstering economic activity.

TN is among one of the highest-performing states in India in terms of the Human Development Index (HDI) has seen significant improvement over the years in social indicators like education and healthcare. TN also has a legacy of social reform programs & it has been pioneering in social welfare programs. Although compared to other states TN’s performance is better, there are disparities in this success story. Gender roles and expectations continue to shape societal norms, influencing labour force participation patterns. Caste dynamics, prelevant in many aspects of life, also impact economic opportunities.

He pointed out certain important facts about the TN Labour Force patterns based on various public data. Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) per thousand individual population, Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) [https://microdata.gov.in/

2023 TN estimate is 54.7%. He mentioned that between 2001-2011 the proportion of persons who are not working in the state increased from 30.30% to 31.16%. Rural LFPR for men saw a gradual decline from 897 in 1993-94 to 838 in 2021-22, while rural LFPR for women in the same period declined more sharply from 680 to 530. The general national trend of increasing unemployment holds for TN also with 1.6% in 2011-12 to 3.6% in 2018-19.

He went further about characteristics of labour in TN with an emphasis on the young people (15-35 age group) who consists 35% of the state’s population. 7 out of 8 workers in TN work in the non-farm sector, with most of them being contract workers with a ‘footloose nature’ [https://www.amazon.in/

He ended his talk with certain criticism about the Dravidian model, especially on urban land usage and urban poverty, despite its relative success compared to other northern Indian states in terms of HDI. Dravidian model promoted urbanization through industrialization, increased infrastructure investments, introduction of pump sets for irrigation, creation of co-op societies, and so on to change caste-based occupations & caste discrimination, supported by social justice policies. In the process, urban areas are getting overcrowded, and more & more slums and in some cases, caste-based settlements are arising in urban areas. There is a repeating trend of slum clearance by the govt which has deprived youths of livelihood opportunities. Govt is planning to create a land bank of 45k acres in the next five years to attract investments, but there is nothing for the workers even in MOUs.

Journalistic Ethics and Labour Journalism:

The speech by Vidyasagar was followed by shorter talks by two in-house journalists of Workers’ Unity, namely Vaishnavi and Sandeep. They shared their insights on certain ethical issues while covering labour struggles and also a few minute but technical aspects that need to be kept in mind.

Vaishnavi used a video footage from a mainstream media covering a particular strike of women workers. She emphasized with particular examples how the reporting of that media is actually reporting from an angle of industry that production is being stopped, and not from the perspective of workers.

That’s why they didn’t take any in-depth interviews of workers there. They also didn’t ask the question about wages and working conditions in their report and what objective causes might have created so much anger among the workers. The entire environment was very emotionally charged and Vaishnavi emphasized that covering the story from a working-class lens doesn’t mean getting carried out by the emotions of workers also. A responsible labour-journalist must independently verify the claims made by workers also.

Sandeep said that at a time when rapid changes in the economic organisation is leaving the workers perilous, the journalistic resources, human and infrastructure, is scantily deployed to cover issues of labour relations. In other words, the ‘Labour Beat’ has been missing at a time when it is dearly needed.

Young journalist should come forward and cover the untold stories burried behind factories workshops around the country.

After this, there was a lunch break and a closed session for the pre-registered participants started after lunch.

Aparna’s Speech on Making Video Stories & various ethical issues:

The session after the lunch started with an “ice-breaking session”. In this session the participants were first asked to get familiar with the space by walking through the whole space and pausing periodically. Then they were asked to form pairs with someone they don’t know already and talk in pairs for sometime. After that they were asked to take the identity of other person in the pair and introduce the other person as self. We later came to know from the organizers that such a “ice-breaking session” is common practice in theatre circles.

Following this there was a talk by Aparna Ganesan on methodology involved in making a video story. At this point a brief introduction of Aparna is required for the reader.

Aparna Ganesan is an independent journalist and documentary filmmaker from India with five years of experience. She’s worked with DW News, Faultline Videos, Mongabay, and Asiaville. Aparna is a 2022 Earth Journalism Network Grantee and 2024 GRID ArendalGrantee. She’s one among ten journalists selected by the East-West Centre to do an Indian-Pakistan cross-border documentar

Intersectionality in demography:

It was interesting to see that the organizers made a great deal of effort towards ensuring the participation and active engagement of interested persons from diverse backgrounds.

The small groups in the interactive sessions were made such that each group contains one person from the trade union/activist background, one student and one person already with some prior exposure to the process of making a video story for journalistic purposes. Such an intersectional interaction made the session more lively where everyone can learn from the experiences of a person with a background drastically different from theirs.

For example, for the activist or trade union leaders, it was learning about how to actually engage with a journalist to get their stories of lives, livelihoods, and struggles out to the broader audience in an empathetic but objective manner.

For the aspiring labour journalists, the feedback from activists/ trade union leaders created a great deal of sensitization about which angles of an actual story of the working class get neglected in the mainstream media, and how to ensure that correct questions are being asked, the correct person is being talked to for an objective but a people-centric story.

Nearly half of the participants of the program were momen from the younger generation. They actively participated throughout the whole program. Aparna, an acclaimed, bold female journalist laid the foundation for the interactive session of the workshop. It is expected that greater participation of women in the labour beat journalism will bring greater sensibilities towards certain aspects of gendered exploitation of capital like the gendered wage gap, gendered physical/sexual violence by employers, etc.

Question of accessibility & inclusivity:

A particular emphasis must be given and the reader’s attention must be drawn to the choice of venue. The entire space was disability-friendly by its architecture. This was to ensure that for any person interested in labour beat journalism and its role in the society, the status of physical disability doesn’t become a barrier to participation. It was good to see that two persons with physical disability indeed joined the program and actively participated in the program throughout the day.

It is also important to notice that the toilets in the venue were gender-neutral. This made the event inclusive for persons of all genders including transgender persons.

Many individuals, especially those who are coming from repressed identity groups in particular or marginalized social groups in general, feel social anxiety in any kind of group activity along with unknown persons. In this regard, the “ice-breaking session” was actually very helpful. It helped to demechanize the interactive sessions and have a fruitful engagement.

About WU, the organizer of the event:

At this point, we must mention about the Workers’ Unity and Workers’ Unity Tamil team, whose mental labour and actual legworks regarding the meticulous planning and execution of the various aspects of the program helped to materialize it to a success.

Workers Unity is an independent and impartial digital media platform dedicated to the struggles of the toiling masses and their achievements and awareness within them. At a time when there is a campaign to create parallel media from within every section, community and class, the need for a dedicated media of working people is being strongly felt. With the introduction of neoliberal policies, the shrinking of print media and the emergence of the electronic medium, it is seen that the labour beat is almost over.

Some journalists, social workers, trade union activists, students and teachers from Delhi initiated Workers’ Unity in 2018 with the aim to become ‘The working peoples’ own media’. With the digital platform becoming more effective and print media shrinking, it was decided that media channels such as YouTube channel, website,

Facebook page, should be used to spread the news. It has extensively covered issues related to lives and livelihoods of working class, farmers, women, adivasi and unemployed persons in the Hindi belt. It has also covered many major struggles of national scale.

One of the biggest achievements of the Workers Unity so far have been the nearly 14 month long continuous extensive ground reporting of the historic farmers’ movement against the pro-corporate farm bills. They took the interviews of various activists and leaders of farmers organisations, agricultural labourer’s organisations, as well as academicians and journalists. This not only amplified the movement’s reach but also have a huge archival value for anybody interested in the agriculture, rural economy, political economy of agriculture and people’s movements etc. One can access these interviews and video reportings in the following playlist.

In collaboration with Groundxero and Notes on Academy, this resulted in publishing a book called the “Journey of Farmers Rebellion”. One can buy this book in the e-book format from the following link. One can also buy the physical copy of the book from the following link.

The prsent workshop was organised mainly by Workers’ Unity Tamil, with constant support from it’s Delhi team. Workers Unity Tamil was created in the early 2023 as a Taminadu Chapter of Workers’ Unity. In it’s one year journey, it has covered extensively on the struggles of both organised and unorganised workers and broader social issues of working class interest. One can access the Youtube channel of Workers’ Unity Tamil through the following link. The Facebook page of Workers’ Unity Tamil can be accessed through following link.

Praises, Criticisms, and Looking Forward:

Many aspects of the program were highly praised by the participants and the observers. The organizers’ great deal of care towards many minute things like the acoustics of the program hall, the timely arrival of lunch, accessibility of the venue, inclusive and intersectional approach towards keeping the program highly interactive and engaging, etc were appreciated by almost everyone we could talk to. Many activists and trade union leaders think that in the era of monopoly capital’s takeover of media and vanishing labour beat, the very initiative towards organizing an event focussing particularly on labour beat deserves huge appreciation.

However, there were some genuine criticisms raised by some participants and observers of the event. It was argued that an event like this owing to its rarity in the modern media ecosystem needed much larger publicity. It was argued that more people from the journalistic fraternity who are interested in reporting people’s movements could have been invited. It was also argued by some participants that the event needed a larger targeted campaign among the students and aspiring journalists. Some participants argued that the program schedule was a bit too heavy for a day. Suggestions were made to either break it into a more than one-day event or reduce the amount of material covered.

As it seems, the organizers are quite open to addressing these criticisms in any future iteration of the program. They also acknowledged that part of these issues also pertain to the fact that a very small team with limited resources is working consistently through it. They think that that is also the reason that more young people need to get engaged in initiatives like Workers Unity, in terms of contributing through their work or any other form of monetary, or logistic help. Ultimately a Workers’ media can only be sustained through people’s resources.

The success of any such program will ultimately be measured in terms of its long-term effects – how many young aspiring journalists dedicate themselves to labour beat, how much it impacts the ethics of individual journalists covering people’s struggles, how many similar chains of events it triggers in the future in the alternate media landscape, how it enables working-class leaders for a better engagement towards media, etc —- the list goes on. The hard reality of today’s repressive times forces one to think that, in order to truely beat the monopoly capital with labour beat, it’s not just a matter of a singular event, but many many such independent initiatives from different sectors and sustained long term intersectional engagement will be required.

Main Events of the Program:

The program started around 10 O’clock in the morning. The program of the whole day was divided into two parts.

The morning session was open to all. It consisted mainly of lectures by luminaries in the field of people-centric journalism and labour economy.

The first speaker in the open session was an eminent journalist and the founder of the People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI) P Sainath. He is also the author of the highly celebrated Raman Magsaysay award-winning book “Everybody Loves a Good Drought”, which documented the hardship faced by the working people in the rural economy by extensive travel through the 30 most economically down-trodden districts of India.

The second speaker of the open session was R. Vidyasagar, who has over the last 45 years been involved in various capacities on issues related to the juvenile justice care system, child sexual abuse, child marriage, trafficking of children, and child bondage. Since 2015, he has been working on issues related to migrant workers of Tamilnadu, which is one of the major in-migration hubs in India.

Vidyasagar’s talk was followed by two short talks by Vaishnavi & Sandeep Rauzi, founding editor of Workers’ Unity.

Do read also:-

- Gig workers: Regulating Work Platforms, exposing Algorithms

- Labour in ‘Amrit Kaal’ : A reality check

- Discovering the truth about Demonetisation, edited and censored, or buried deep?

- Class Character of a Hindu Rashtra- An analysis

- Gig Workers – Everywhere, from India to America, from delivery boys to University teachers

- May Day Special: Working masses of England continue to carry the spirit of May Day through the Year

- New India as ‘Employer Dreamland’

- Urgent need for reinventing Public Sector Undertakings

Subscribe to support Workers Unity – Click Here

(Workers can follow Unity’s Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Click here to subscribe to the Telegram channel. Download the app for easy and direct reading on mobile.)